SIGNAL DEPT EDITION 13

The Studios That Split Sound in Two: Musique Concrète, Elektronische Musik, and the Birth of Modern Sonic Practice

You’ve tuned into the transmission. Welcome to the feed.

Signal Dept. is a human-filtered electronic music digest — equal parts playlist, field report, and zine. We trace signals from the underground: experimental EPs, Bandcamp drops, small-run vinyls, and producers working just outside the algorithmic frame.

Each edition moves between listening and investigation — mapping how scenes form, who’s pushing sound design forward, and what connects the frequencies emerging from bedrooms, basements, and backrooms across the world.

We’re not optimising for clicks or chasing hype. We’re documenting signal strength — and the people who keep broadcasting it.

In this edition:

Signal Scan Track Notes

Part 4 — The Studios That Split Sound in Two: Musique Concrète, Elektronische Musik, and the Birth of Modern Sonic Practice

From the series: From Telharmonium to Techno — A Technical History of Electronic Music

SIGNAL SCAN TRACK NOTES

Each edition highlights a handful of tracks worth pulling into rotation — selections that reveal how producers are shaping low-end, texture, and atmosphere across electronic subcurrents. No algorithms, just human-filtered signals.

Find these and many more tracks on the YouTube playlist: Signal Dept - Electronic Music New Releases

The playlist features songs across various genres and sub-genres of House, Tech and Electro. There are several established acts but the focus is on the lesser known artists.

DESCENT by ODDO

Melodic Techno with great string arrangement

Eureka by Guy J

Progressive, great groove and some immersive dark layers

Diafana by Simon Vuarambon

Melodic with rich sound design

Dope Riddim by Mike Rish

Mid-tempo Progressive and dirty

Dope Groove by K Loveski

2nd track this week with “dope” in the name but distinctly different :) Nice track with some interesting things happening in the bass line

Part 4 — The Studios That Split Sound in Two: Musique Concrète, Elektronische Musik, and the Birth of Modern Sonic Practice

From the series: From Telharmonium to Techno — A Technical History of Electronic Music

Electronic music’s lineage often reads like a parade of technologies—oscillators, filters, sequencers, drum machines, samplers—marching toward the modern studio. But the mid-20th century introduced a different kind of rupture, one not defined by machines alone but by two incompatible philosophies of what sound could be. One side began with the world itself: recordings of trains, kitchenware, voices, footsteps, and industrial hum. The other began with pure tone: sine waves, test oscillators, pulses, and electronic signals with no acoustic origin. These two ideologies—musique concrète in Paris and Elektronische Musik in Cologne—split the material of electronic music into two streams that would later recombine in nearly every modern genre.

Part 4 traces that divergence. It examines the studios, the tools, the listening practices, and the philosophical commitments that shaped mid-century experimentation, and shows how their collision eventually built the foundation for everything from synth-pop and techno to sampling culture and modern sound design.

1. Paris, 1948 — Schaeffer and the Birth of Musique Concrète

In 1948, former radio engineer and broadcaster Pierre Schaeffer began a series of experiments at the French Radio and Television (RTF) studios that pushed beyond the boundaries of traditional composition. Working initially with turntables and later with magnetic tape, Schaeffer built music out of recorded sound fragments—a railway engine, a spinning pot lid, a struck piano string, a child’s voice slowed to a ghostly drawl.

The term he coined, musique concrète, was a deliberate provocation. “Concrète” implied the opposite of abstraction. Instead of writing notes for instruments, the composer worked directly with sound objects (objets sonores), treating them as raw material to be carved, layered, reversed, and transformed.

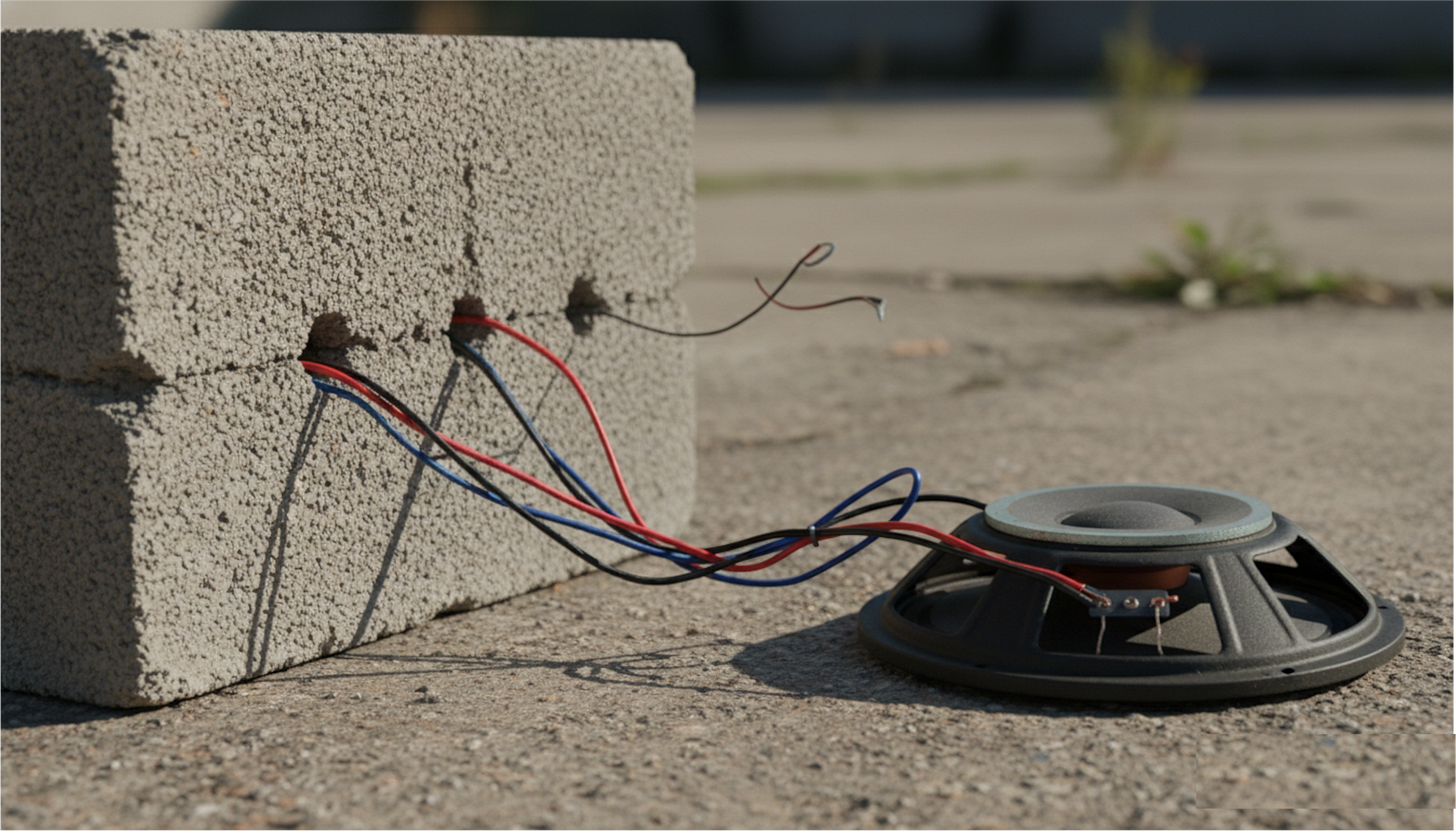

The early RTF studio was a playground of mechanical ingenuity:

Disc cutters for recording short takes

Locked-groove turntables for primitive looping

Variable-speed turntables for pitch and time manipulation

Filters, reverbs, and equalizers for spectral shaping

And eventually, magnetic tape machines allowing unprecedented control

Techniques that DJs, producers, and sound designers now take for granted—editing, looping, time-stretching, montage—were invented here through laborious, hands-on craft. A single cut required razor blades, leader tape, wax pencils, and almost surgical precision.

But musique concrète was never just about technique. It was a revolution in listening. By stripping sounds from their sources, Schaeffer asked listeners to hear them anew, without narrative or visual cues. This acousmatic stance—sound without source—became a foundational principle of electronic music aesthetics.

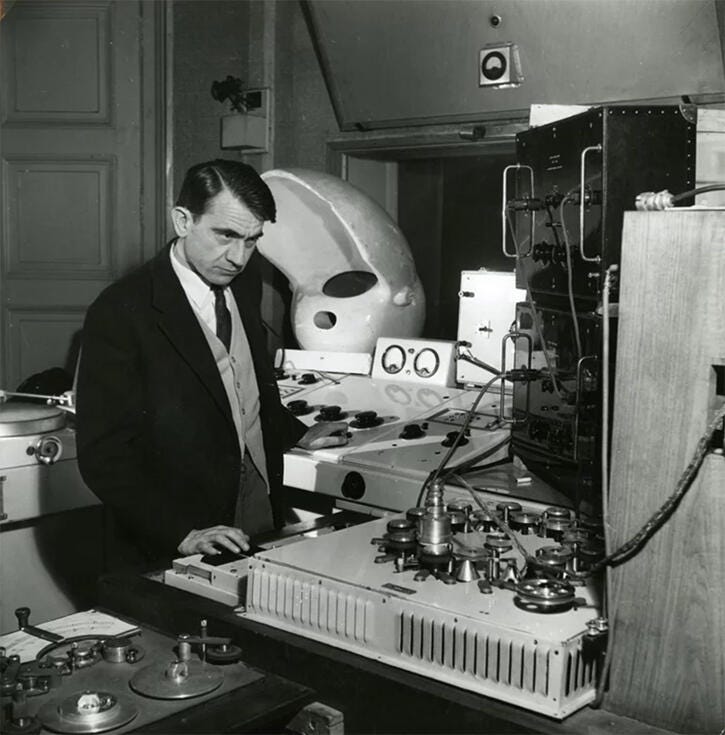

2. GRM and the Institutionalization of Sonic Experimentation

By the late 1950s the experiments crystallized into an institution: the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM), founded by Schaeffer and later joined by figures such as Pierre Henry, Luc Ferrari, François Bayle, and others. GRM was part laboratory, part school, part artistic collective. It formalized the idea that electronic composition was a new discipline requiring its own tools, theories, and pedagogy.

GRM developed purpose-built devices such as:

The phonogène, a variable-speed tape playback instrument with keyboard control

The Morphophone, a multi-head tape delay system enabling dense textures

Custom filters and mixing consoles designed for acousmatic music

Advanced splicing blocks and synchronization systems for complex editing

More importantly, GRM cultivated a methodology. Composers were encouraged to explore sound as material—touching, cutting, rearranging, and transforming recorded fragments until they revealed new musical identities. Sound was no longer symbolic; it was tactile.

While the Telharmonium hinted at the idea of tone as a constructed artifact, the GRM studios made sound itself into a physical substance, malleable and expressive.

3. The Acousmatic Idea — Listening Without Seeing

Central to Schaeffer’s philosophy was the notion of acousmatic listening, inspired partly by the Pythagorean tradition of students learning behind a veil. Acousmatic listening suspends the visual source of a sound, allowing perception to focus on its internal qualities: mass, grain, envelope, spectral shape, attack, decay.

This separation is easy today in headphones, sample libraries, and DAWs—but in 1948 it was radical. It shifted music away from performance and toward auditory phenomenology, where meaning arises from the morphology of sound itself.

Acousmatic thinking remains embedded in modern production:

A kick drum sample is judged by weight, transient sharpness, and tail—not by the drum it came from

A field recording becomes atmospheric texture rather than documentary evidence

A chopped vocal becomes a hook even if the original phrase is unrecognizable

The contemporary studio is acousmatic by default. Schaeffer simply gave language to a way of hearing that electronic culture would later universalize.

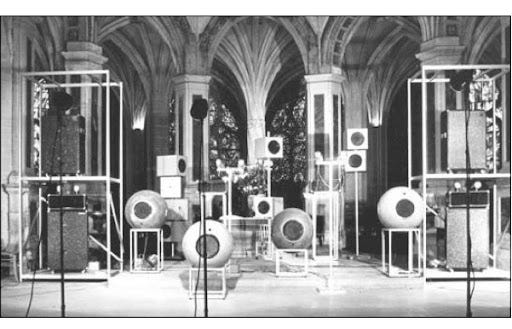

4. The Acousmonium (1974) — A Loudspeaker Orchestra

One of GRM’s most ambitious inventions was the Acousmonium, created by François Bayle in 1974. Unlike a traditional PA system designed for uniform coverage, the Acousmonium was conceived as a loudspeaker orchestra: dozens of speakers—each with distinct size, tone colour, and dispersion—arranged throughout a performance space.

During concerts, a performer (the “diffuser”) used a multi-channel console to project sounds to specific speakers, highlight timbral details, or send sonic gestures sweeping across the room. The Acousmonium turned playback into live performance and elevated spatialization to an essential musical parameter. It was a physical manifestation of acousmatic thought: sound detached from source, sculpted in motion.

5. Across the Rhine — Elektronische Musik and the Pursuit of Sonic Purity

While Paris embraced the messy richness of recorded sound, German studios pursued the opposite ideal. At the Studio for Elektronische Musik in Cologne—established in the early 1950s under Herbert Eimert and later shaped by Karlheinz Stockhausen—composers sought a music built from pure electronic tones, created from scratch rather than captured from the world.

Where musique concrète asked “What can we do with the sounds we find?”, Elektronische Musik asked “What can we build from first principles?” The Cologne studios were filled with:

Sine-wave oscillators

Noise generators

Pulse and sawtooth wave sources

Filters, ring modulators, and envelope shapers

Early sequencing and control systems

Works like Stockhausen’s Studie II explored mathematically structured relationships between frequency, duration, and timbre. Every parameter could be calculated, measured, and controlled. Sound was abstract, idealized, and precise.

This laboratory ethos profoundly influenced academic electronic composition, but it also seeded the logic behind synthesizers, modular systems, and later algorithmic and FM synthesis—sound as a construct rather than a capture.

6. The Legacy: From Tape Manipulation to the DNA of Modern Production

The GRM studios were slow, manual, and labour-intensive, yet the techniques pioneered there—montage, looping, reversal, filtering, and time manipulation—became the core vocabulary of contemporary electronic music. These gestures reappear today in the DAW timeline, the sampler, the clip editor, and the automation curve.

But the deeper inheritance is methodological. GRM introduced a mode of composition based on listening into materials, discovering expressive potential within recorded fragments. Modern producers—from hip-hop beatmakers to techno sculptors to film sound designers—still rely on this approach. The tools have changed, but the logic has not: music emerges from interacting with recorded sound as a malleable substance.

7. The Aesthetic of the Fragment: Recontextualization as Creative Engine

Schaeffer’s most enduring insight is that fragments are fertile. A sound, once severed from its source, becomes a plastic object capable of countless reinterpretations. This idea underlies nearly every sample-based practice of the last fifty years.

Hip-hop’s chopped breaks, jungle’s sliced Amen loops, techno’s vocal stabs, ambient’s stretched field recordings, Autechre’s re-buffered micro-samples, glitch’s deliberate ruptures—all treat the fragment not as a remnant, but as a primary unit of creativity. Meaning arises from context, juxtaposition, and transformation.

Musique concrète didn’t just propose a new technique; it reframed fragmentation itself as a generative aesthetic, a way of thinking about sound that modern culture has absorbed into its bloodstream.

Conclusion: Schaeffer’s Real Revolution — A New Ontology of Sound

Musique concrète’s revolution was not the invention of tape manipulation—others would have discovered these techniques eventually. Its significance lies in its philosophical stance: sound as material, composition as transformation, listening as primary inquiry.

Schaeffer replaced notation with manipulation, instruments with recordings, and abstraction with phenomenology. He repositioned the composer as a sculptor of audio itself. Today’s workflows—from sample chopping to spectral morphing—are built on that ontology.

The mid-century split between concrete and electronic approaches was not a divergence but a creative tension. When these strands later rejoined—in modular synthesis, pop studios, club music, and digital production—they formed the hybrid ecosystems of contemporary electronic music. The world of techno, ambient, EDM, hip-hop, and experimental sound art is built from this fusion of captured and constructed sound.

Next in the Series — Part 5: The Artists Who Turned Technology Into Genre

Part 5 moves from studios to people: the pioneers who transformed abstract techniques into cultural movements. We’ll explore how early innovators—Wendy Carlos, Delia Derbyshire, Kraftwerk, Laurie Spiegel, Morton Subotnick, Suzanne Ciani, Giorgio Moroder, Brian Eno, Juan Atkins, Frankie Knuckles, Jeff Mills, New Order, and others—took tape manipulation, synthesizers, drum machines, sequencers, and early computer systems and turned them into genres, subcultures, and enduring musical identities. From the Moog to the MPC, from minimalism to house and techno, Part 5 shows how technology becomes culture through the hands of visionary musicians.

also read:

Part 1: SIGNAL DEPT EDITION 10 - From Telharmonium to Techno: A Technical History of Electronic Music

Part 2: SIGNAL DEPT EDITION 11 - The Colossus That Wanted to Stream: Cahill’s Telharmonium and the Birth of Music as a Utility

Part 3: SIGNAL DEPT Edition 12 - The Micro-Architectures of Sound: Fourier, Harmonics, and the Synthesis Grammars that Built Electronic Music

Signal Dept. chronicles culture that refuses commodification. Field reports and scene intel: theswingcafe@gmail.com

Find Signal Dept on Bluesky and YouTube

[END OF SIGNAL DEPT. — Edition 13]